The concern surrounding meat consumption involves four key themes:

1) The recognition of farm animals’ capacity to suffer;

2) The shift towards increased consumption of white meat;

3) The way animals are farmed; and

4) The psychological, societal, and systemic factors that cause us to ignore, downplay, and justify farm animal suffering.

Farm animals’ capacities to suffer

Prior to getting into the behavioural side of meat consumption research, I focused my efforts on understanding animal suffering by studying their sentience and cognition, particularly that of chickens.

This isn’t to suggest that chickens are brilliant animals—though they show some surprising cognitive abilities—but something a lot simpler. They can experience stress, fear, and pain, which should be enough for us to take seriously how we treat them. Not because they are like us, but because their capacity to suffer makes their wellbeing morally significant, especially since we create the conditions of their lives.

The shift towards white meat

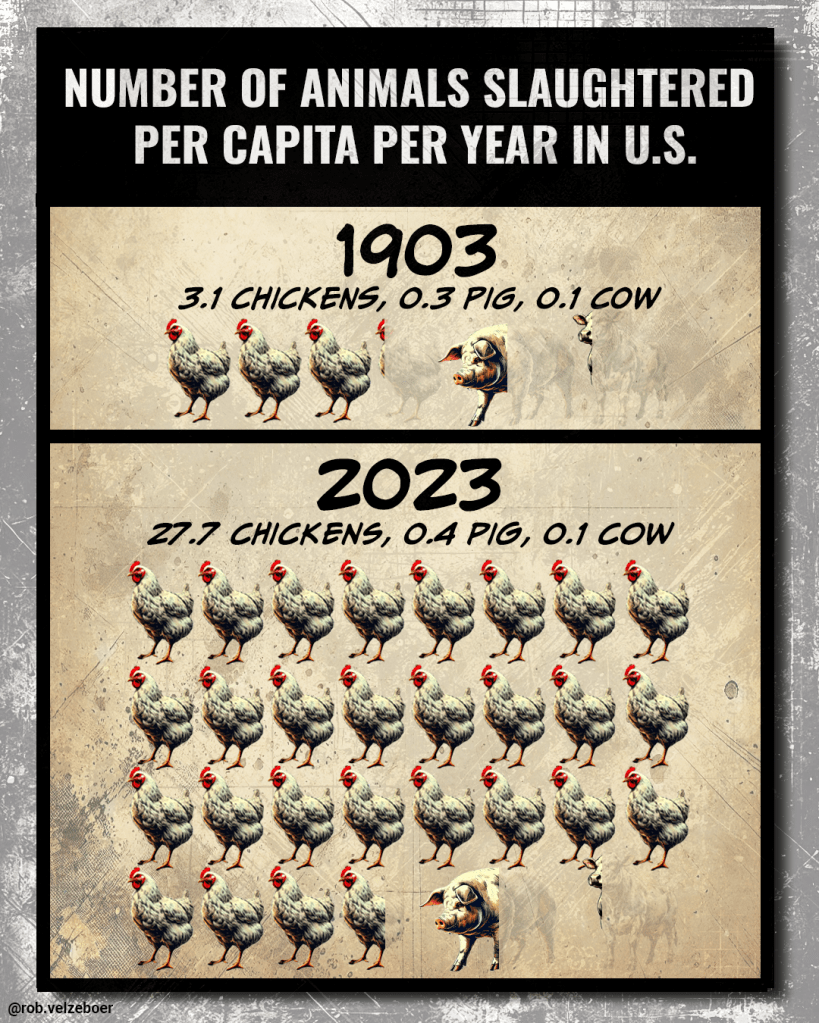

Meat consumption patterns have shifted strongly toward white meat in the past century.

This shift is driven by affordability, health, and environmental considerations. Advances in industrial farming have made chicken one of the cheapest and most accessible protein sources, while its leaner nutritional profile appeals to consumers looking to reduce their intake of red meat. Environmentally, chicken has a smaller carbon footprint compared to beef or pork. Combined, these factors make chicken the dominant meat choice in many diets, replacing the central role red meat held in earlier food cultures.

This is a serious welfare concern not only because of the number of chickens that need to be killed to procure a significant amount of meat—in 2023, Americans slaughtered 274 and 76 times as many chickens as they did cows and pigs, respectively—but also the lack of legal protection and poor welfare standards for chickens. Indeed, animal welfare standards are argued to be worst in the production of poultry and eggs, comparably bad for pork—though these animals are slaughtered in much lower numbers, but significantly better for beef and dairy.

How animals are farmed

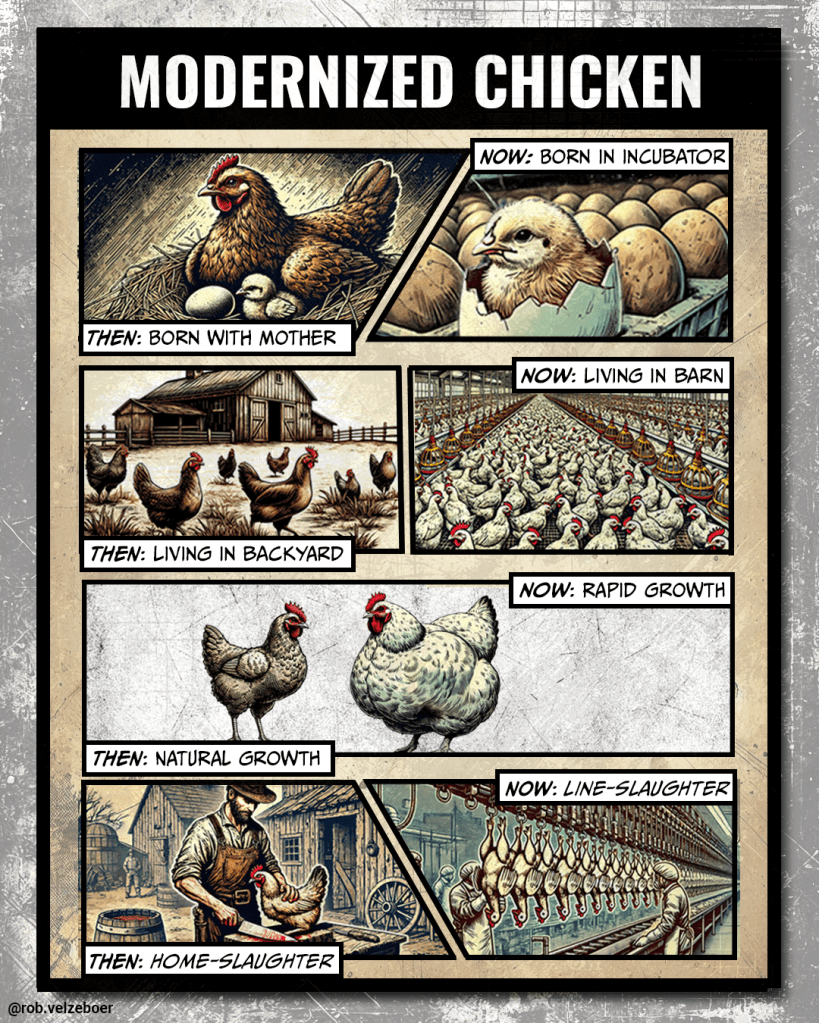

Animal farming practices—and by extension animal welfare—changed dramatically in the 20th century.

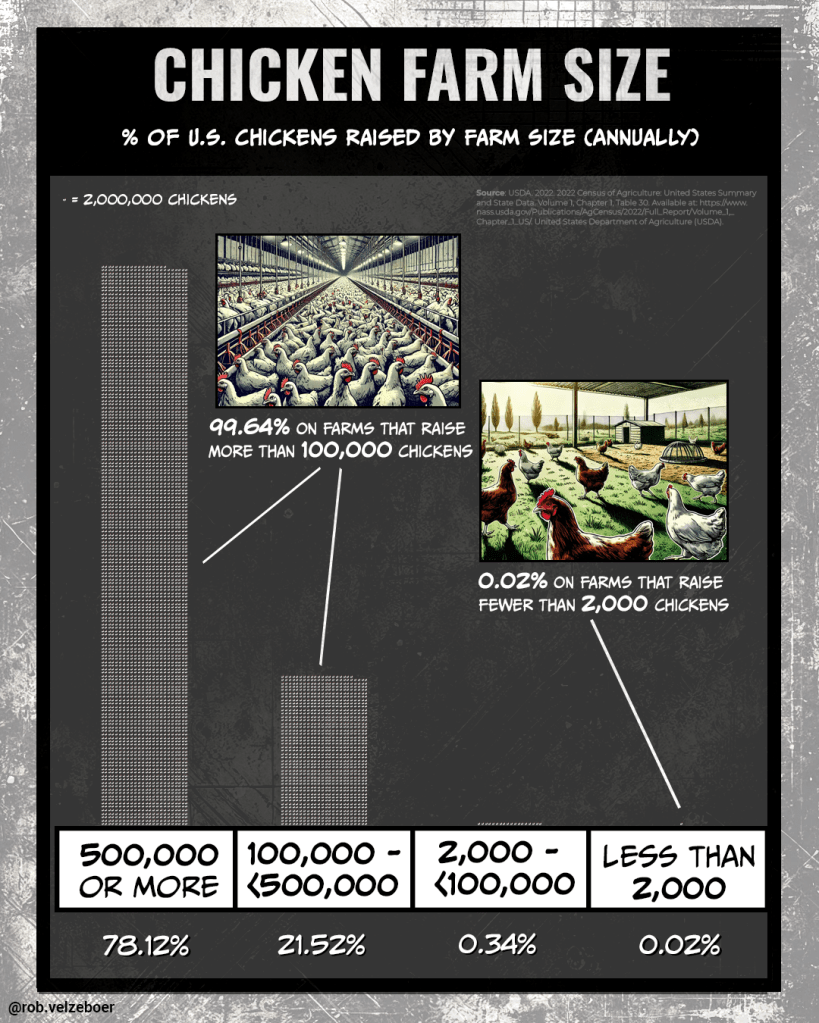

Advances in technology and mechanisation allowed for much more efficient meat production, driving smaller farmers out of business. Farmers’ pay became tied to corporations, who control the inputs and production, reducing farmers’ independence, with a small number of farms producing massive numbers of animals. This concentration has made industrial farming the dominant model.

Large profit-driven operations replaced smaller farms in the span of a few decades. In hog farming, for example, in just 35 years the number of farms reduced by more than 90 percent, where small farms came to produce a negligible share of the overall meat that is consumed. For meat chickens (broilers), 99.6% of them are now raised on farms growing over 100,000 a year, with less than 0.1% of chicken meat coming from small-scale farms.

In this shift, traditional farming practices disappeared and were replaced by ones focused on efficiency. Chickens, once raised with their mothers in backyards or small farm houses, are now born in incubators after several rounds of selective breeding and crowded into large barns, where they grow at artificially accelerated rates before being killed on automated slaughter lines that prioritise speed and volume.

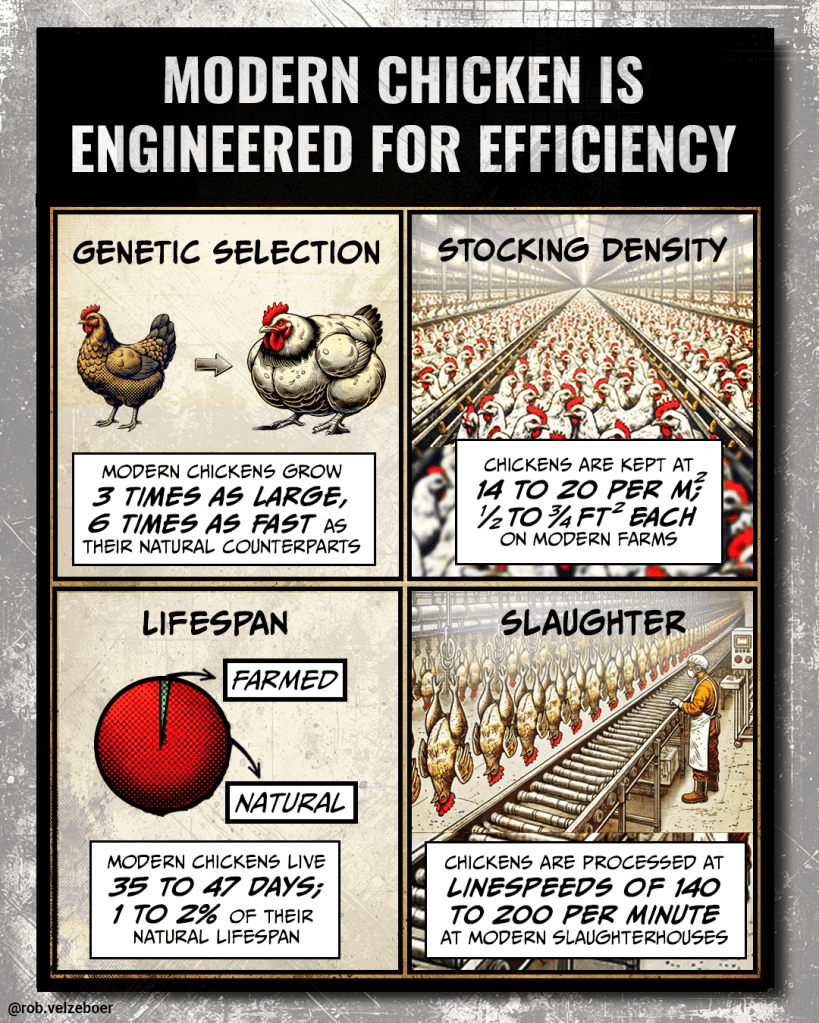

The main welfare considerations in this system are genetic selection—chickens growing rapidly due to selective breeding; stocking density—chickens being kept in high-density barns designed to optimise production; lifespan—chickens’ lives are very short, lasting just a few weeks; and mass slaughter—chickens are processed at high speeds, creating the risk of rough handling and improper stunning.

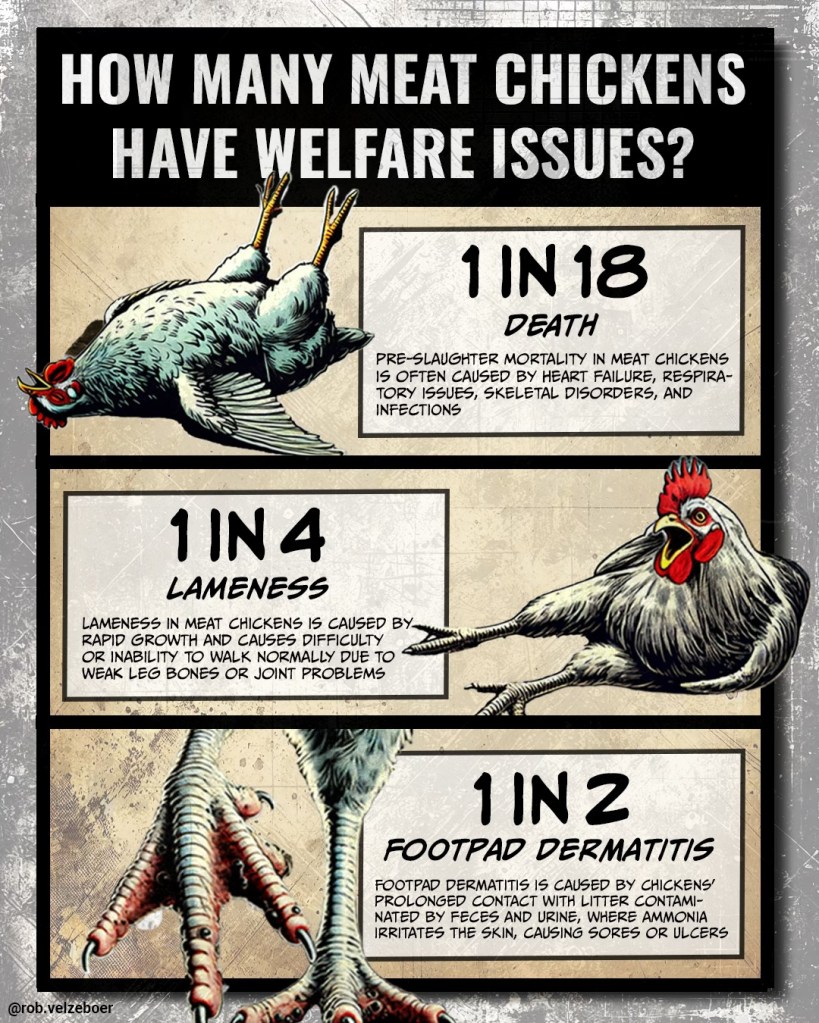

These intensive farming practices have led to widespread welfare issues. Rapid growth frequently results in lameness, making movement difficult or impossible, while overcrowded living conditions often cause footpad dermatitis due to constant contact with chickens’ own and each other’s waste. Mortality due to heart failure, respiratory issues, and infections is also high and has steadily increased in the past decade.

Why no one cares

Most people don’t notice or think about these issues because they are far removed from the process. Modern food systems keep the realities of farming hidden, while convenience and price drive consumer choices, making it easy to ignore how animals are raised and processed. My PhD research specifically focuses on men’s attitudes towards meat reduction and meat alternatives, as they consume significantly more meat than women, use different justifications for doing so, and are more strongly influenced both culturally and by commercial interests.